“In economics, things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could.” ~ Rudiger Dornbusch, former MIT Economist

Prologue

The bear market of 2022 was driven by investors anticipating a recession this year. Of course, there will eventually be another recession, but so far, the global economy continues to defy the gravity of higher interest rates.

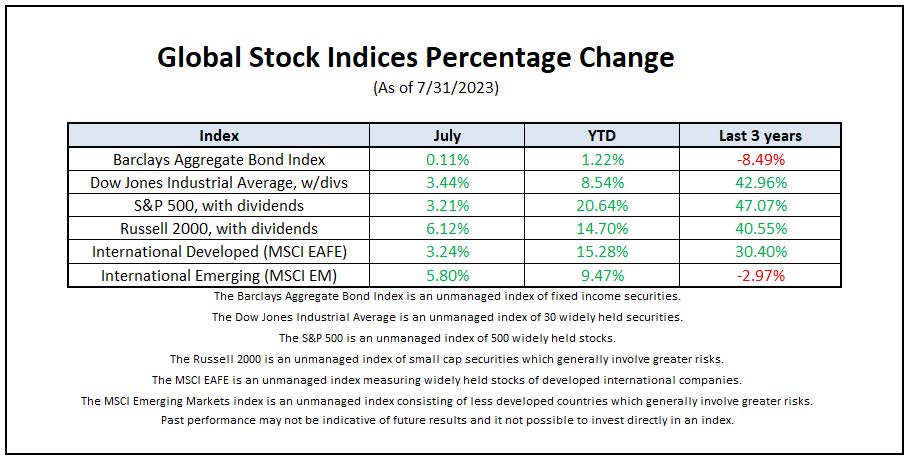

After all the debate last year about soft or hard landings, markets almost appear to have lost interest in the economy. Despite higher interest rates than expected, government bond yields are largely unchanged on the year. As for stocks, the rebound we saw commence in Q4 2022 has been sustained thanks in part to a resilient labor market and sudden infatuation with all things AI (artificial intelligence). Big tech US large caps are still widely outperforming in 2023 (Nasdaq 100 up over 44%), but the rally has been broadening over the past two months with US small caps, Emerging Markets and Value stocks joining in.

The big game-changer for investors in recent years, apart from the re-emergence of inflation, has been the aggressive counter-stance taken by central banks. For decades, investors could rely on them to support markets. Now, in their fight against inflation, they acknowledge that their rate policies will hurt economic growth and financial markets.

What’s an investor to do?

First, for fixed-income investors, it is now possible to build an attractive liquidity reserve with relatively low risk. Given the shape of the yield curve, investors should not have to stretch their maturity or credit profile to achieve admirable yields.

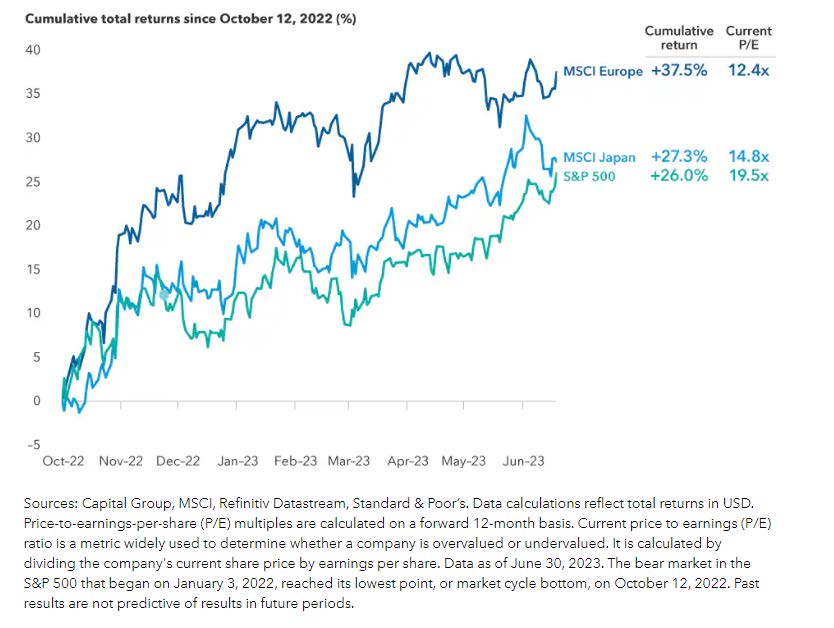

For equity investors, we may have seen the bulk of this year’s index returns already. But as we have already seen, if the eventual economic landing is pushed out further again, the market can continue to run. Also, this year’s returns have come from a very narrow range of stocks. While such narrow rallies preceded reversals in the past, today’s valuations are not particularly stretched outside of the US mega-cap leaders, and therefore there is plenty of room for other stocks to grow from here.

The obvious lesson from recent years though should be not to invest according to economic forecasts. So even though the next recession is always getting closer, trying to predict and time it is less useful than constructing a portfolio that can weather different economic conditions. And the good news is that markets now offer us better choices than we’ve had for some time.

Please reach out with questions.

- Paul

Noteworthy links:

- Vanguard: Higher inflation not the end of the 60/40 portfolio

- RBA: One for Millennials and Gen Z

- American Funds: Can this stock market rally continue?

Chart of the Month

Major stock markets have soared more than 25% from bear market lows

Article of the Month

The Recession Questions: Yes, No, When and How Bad?

By David Kelly, Chief Global Strategist at JP Morgan Asset Management, published June 20th, 2023.

One of the advantages of being back in the office, when I am actually in the office, is I get to hear a variety of opinions. These opinions are sharply divided today on the issue of a U.S. recession. One camp feels that recession is inevitable. Another sees a path to a “soft-landing”. Of course, this argument really refers to a recession starting in the next quarter or two. Sooner or later, a recession will occur. However, that brings up other questions, namely, when will a recession start, how deep will it be and how long will it last?

No one should claim certainty in answering these questions. Changes wrought by more than a decade of super-low interest rates, followed by the radical impacts of the pandemic, make it very difficult to assess either the innate resilience of the economy or how it is being impacted by the Fed’s aggressive tightening. However, as of now, the odds seem to slightly favor avoiding recession through the end of 2023 but not through the end of 2024. Whenever a recession occurs, it will most likely be much milder than the last two economic downturns. However, partly because of this, any recovery would likely be very weak, allowing for a continued downward drift in inflation, interest rates and the dollar, with important implications for long-term portfolios.

Near-term Recession: Yes or No?

Before addressing the recession questions, it’s important to get definitions straight. Contrary to popular belief, a recession is not defined as two consecutive quarterly declines in real GDP. Rather U.S. recessions are retrospectively declared to have started or ended by the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research. Recession, as defined by the Committee, is a significant decline in economic activity, spread across the country, lasting more than a few months and manifesting itself in declines in real personal income outside of transfers, employment as defined by both the household and payroll surveys, real consumer spending, real retail and wholesale sales and industrial production.

By this yardstick, the economy did not fall into recession in 2022, despite declines in real GDP in both the first and second quarters, since employment grew very strongly throughout the year. Moreover, while economic momentum continues to slow in 2023, it still appears to have been broadly positive in the first half of the year. Indeed, following a 1.3% annualized gain in the first quarter, real GDP growth is tracking a pace of between 1% and 3% for the second. But what about the second half of the year?

Looking first at real GDP, so long as the economy suffers no further major shocks from here, we may see continued slow economic growth at least through the end of 2023. On the negative side, businesses are likely to cut back on hiring, inventories and capital spending in reaction to tighter credit conditions and recession worries. Consumer spending may also grow more slowly, particularly when student loan repayments are reintroduced this fall. However, offsetting this should be some remaining pent-up consumer demand for autos and business demand for workers. Homebuilding should be close to a bottom, given very low inventory levels and strong demand for multi-family units while moderate growth overseas and a somewhat lower dollar should sustain net trade. Finally, while federal government spending will be constrained by the recently enacted debt-ceiling agreement, state governments should have some room to provide net fiscal stimulus in the form of tax cuts or spending increases.

A similar note of very cautious optimism can be expressed relative to the criteria used by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Given general business caution and weak readings in recent manufacturing surveys, industrial production could fall in some of the upcoming months. The same could be said for real consumer spending and real wholesale and retail sales.

However, the economy is still seeing an extraordinary excess demand for labor, with 1.66 job openings at the end of April for every unemployed worker in early May. While this is down from more than 2.02 jobs per unemployed worker in March 2022, it is still far above the 1.26 prepandemic record set in January 2020. It is this unsatisfied demand for workers, rather than GDP growth over the past year, that has led to strong payroll gains. Economists do not have many decades of U.S. data to assess how job openings should fade in a slowing economy or even how “real” they are, in a world where the act of posting a job opening requires so little effort. However, as of today, the excess demand for labor looks like it may inoculate the economy from declines in payroll employment or substantial increases in the unemployment rate for many months more.

If this is the case, then not only is the economy likely to see continued job growth for some time to come but also solid gains in wage and salary income. We expect CPI inflation to continue to moderate in the months ahead and generally run slightly cooler than wage gains. If this transpires, then real personal income growth should also generally be positive, allowing the economy to maintain a slow expansion.

When Could a Recession Occur?

This suggests a base case of narrowly avoiding outright recession – for now. But if not now, then when?

One way to look at this is to think about the combination of events that normally precipitate recession. Since World War II, there have been 12 recessions all of which were somewhat different. However, generally, three broad conditions seem to have triggered recession: (1) an economy at full employment, (2) some kind of shock and (3) a policy mistake.

The first condition seems somewhat counterintuitive. Full employment is, after all, a good thing. The problem is that, when the economy is recovering from recession and thus re-employing millions of unemployed people, it has extra momentum. When we run out of unemployed people to reemploy, growth necessarily slows and so it takes less of a shock to turn growth into decline. Once GDP begins to fall, businesses and households switch to “recession mode” and, by trying to cut costs, tend to make the recession deeper. Following the same logic, an economy which has weak labor force growth at full employment should be more vulnerable than one with strong labor force growth. Looked at from this perspective, the U.S. economy in the summer of 2023 is certainly vulnerable to recession. Even with a bounce higher last month, the average unemployment rate so far this year is 3.5%, the lowest we have seen since 1969. Moreover, the U.S. population aged 18 to 64 grew by only 0.5% over the past year and is expected to experience even slower growth in the year ahead, suggesting weak labor force growth.

On the second condition, “predicting a shock” is, of course, a contradiction in terms. A shock that is expected is not a shock. However, a better way of thinking about this is to consider how frequently, in the past, the economy has experienced shocks that have proven large enough to put the economy in recession. The average length of the 12 complete economic expansions since World War II has been 64 months or five and a third years. The current expansion, which started in May of 2020, just celebrated its third birthday. Based on this, we are not “overdue” for a recession-causing shock. That being said, shocks do not occur on a set schedule. Given the likely very weak trend in growth, we are just one medium-sized banana-skin away from recession.

On the third condition, the risk of a policy mistake appears very real. Last week, the Federal Reserve decided not to increase the federal funds rate after ten consecutive rate hikes. However, it was a very hawkish pause, with only two of 18 FOMC participants expecting no further tightening before the end of the year, four predicting one further hike and 12 expecting at least two more rate hikes. It appears that the Fed may be contemplating hiking by 25 basis points in July, skipping a September hike and adding a last hike on November 1st. This messaging would have the added advantage of convincing the market that the Fed has no intention of cutting rates this year, even though the “dot plot” shows an intention to implement four cuts in 2024 and five in 2025.

Looked at in isolation, there is a certain symmetry in a hiking cycle that started slowly with a 25 basis point hike in March of 2022, accelerated to 75-basis point hikes for four consecutive meetings in the middle of last year and then petered out to 25 basis point hikes every other meeting in the middle of 2023. It also sounds superficially reasonable right now to “hold the policy rate steady to allow the Committee to assess additional information and its implications for monetary policy” as Chairman Powell explained last Wednesday. However, since monetary policy operates with a considerable lag, the relevant information is not how the economy will perform over the next six weeks but rather how it is likely to be performing a year from now. The Fed may well have already gone too far and further rate hikes in July and November would only make matters worse.

In particular, there continues to be a significant danger from bank credit.

This winter’s regional bank turmoil appears to have subsided. Commercial bank deposits, which fell by almost $500 billion between March 1st and March 29th, have since stabilized. However, a combination of quantitative tightening and more attractive yields on money market funds will likely continue to reduce deposits in the months ahead. On the asset side of bank balance sheets, losses on security portfolios due to higher interest rates are likely to be compounded by credit problems in commercial real estate and small business loans.

All of these problems are likely to worsen for as long as the Federal Reserve maintains its current level of interest rates. This could lead to a renewed bout of turmoil among smaller banks in the fall, particularly among the hundreds of publicly-traded banks which are vulnerable to a “run” on their stock in addition to the more traditional risk of a run on their deposits.

Moreover, even if further turmoil is avoided, banks are growing more cautious in their lending. The April Senior Loan Officer Survey, which covers bank lending practices in the first quarter, showed a net 46.7% of banks tightening lending standards for small businesses, the highest reading since the last recession and a higher reading than for any non-recessionary quarter in the last 30 years. It is worth noting that this tightening of lending standards, (along with the increased cost of credit), is happening at a particularly inopportune time, since many businesses are not profitable in a post-pandemic environment and are consequently very dependent on bank credit.

The impact of all of this could unfold over the next few quarters and could be enough to tip the economy into recession. However, if this proves that the Fed’s aggressive tightening in 2023 was too much, its policy in 2024 is unlikely to help matters. Monetary easing, like monetary tightening, acts with a lag. Small rate cuts in early 2024 could actually slow the economy further, first, because they could spread fear that the economy had finally lurched into recession and, second, because the public would astutely guess that further rate cuts were likely on the way, causing both consumers and businesses to hold off on further borrowing until they could get a better rate. Moreover, this monetary policy drag would likely be compounded by restrictive fiscal policy, since the Republican-controlled House of Representatives would be loath to pass a stimulus bill that could aid a Democratic President running for re-election.

The Depth and Length of Recession

Adding it all up, the factors that are delaying the onset of a recession probably mean that a recession, when it arrives, will be shallow. This is important to bear in mind since the last two recessions were each the deepest since the 1930s. However, it is equally important to recognize that, regardless of the official start and end dates of a recession, recessionary conditions would likely linger.

In part, this would be a reflection of the shallowness of the recession. A recession that doesn’t lead to a big spike in unemployment means that the subsequent expansion will not benefit from the momentum created by the rapid rehiring of unemployed workers. However, in addition, slow growth in labor force should persist, leading to generally sluggish job gains. Monetary stimulus would likely be less dramatic than in previous episodes as the Fed will be wary of reigniting inflation. Fiscal stimulus could also be non-existent until the spring of 2025 and might only emerge in a big way if either the Democrats or Republicans sweep the White House and both houses of Congress in the November 2024 elections. However, for investors, a slow recovery from recession would have an important silver lining. It would likely result in a further erosion of inflation, with year-over-year price gains slipping below the Fed’s 2% target. Such a scenario could result in low long-term interest rates benefiting both stocks and bonds. It also could support a gradual decline in the dollar, amplifying the return on international investments for U.S. residents.

Here is a link to the full article: The Recession Questions: Yes, No, When and How Bad?

*Raymond James & Associates, Inc, member New York Stock Exchange/SIPC

*The information contained in this report does not purport to be a complete description of the securities, markets, or developments referred to in this material, and is not a recommendation. There is no guarantee that these statements, opinions or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct.

*Views expressed are the current opinion of the author, but not necessarily those of Raymond James. The author’s opinions and forward looking statements expressed are subject to change without notice. This information does not constitute a solicitation or an offer to buy or sell any security. Information contained in this report was received from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy is not guaranteed.

*There is no assurance any investment strategy will be successful. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected, including diversification and asset allocation. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. International investing involves additional risks such as currency fluctuations, differing financial accounting standards, and possible political and economic instability. These risks are greater in emerging markets. Small- and mid-cap securities generally involve greater risks and are not suitable for all investors. Asset allocation and diversification do not guarantee a profit nor protect against a loss. Individual investor’s results will vary.

*Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the annual market value of all goods and services produced domestically by the U.S. Past performances are not indicative of future results. Investing always involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss. No investment strategy can guarantee success.

*This information contains forward-looking statements about various economic trends and strategies. You are cautioned that such forward-looking statements are subject to significant business, economic and competitive uncertainties and actual results could be materially different. There are no guarantees associated with any forecast and the opinions stated here are subject to change at any time and are the opinion of the individual strategist. Data comes from the following sources: Census Bureau, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Bureau of Economic Analysis, the Federal Reserve Board, and Haver Analytics. Data is taken from sources generally believed to be reliable but no guarantee is given to its accuracy.

*Links are being provided for information purposes only. Raymond James is not affiliated with and does not endorse, authorize, or sponsor any of the listed websites or their respective sponsors. Raymond James is not responsible for the content of any web site or the collection or use of information regarding any web site’s users and or/members.

*Certified Financial Planner Board of Standards Inc. owns the certification marks CFP®, CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNER™ and Federally registered CFP (with flame design) in the U.S., which it awards to individuals who successfully complete CFP Board’s Initial and ongoing certification requirements.

*The S&P 500 is an unmanaged index of 500 widely held stocks that is generally considered representative of the U.S. stock market.

*To opt out of receiving future emails from us, please reply to this email with the word “Unsubscribe” in the subject line. The information contained within this commercial email has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but we do not guarantee the foregoing material is accurate or complete.

Insights & Discovery