Febuary 26, 2025

Math principles provide confidence to allocate capital into out of favor segments

Decades of experience in the capital markets (plus long-term history) provide confidence to allocate into out of favor segments and then be patient. That said, we never go ‘all in’ on any market segments. That’s because market segments can remain in and out of favor for extended periods of time. Of greater importance, history reveals that diversification is a key ally in the quest for long-term success. Furthermore, I have repeatedly observed that it is generally only a question of time until segments that are inexpensive relative to their own history and other market segments can provide ballast when it’s most needed.

Investment gains are robust when earning per share growth is favorable and valuation (e.g., the PE ratio) expands. I refer to this one-two combination as investment nirvana. The reverse is also true. Sometimes share prices of companies (including those that are well-regarded) perform poorly due to a combination of subpar growth (e.g., EPS growth slows) and a significant decline in the PE ratio. Here is an excerpt from a letter I wrote and shared nearly 1 year ago.

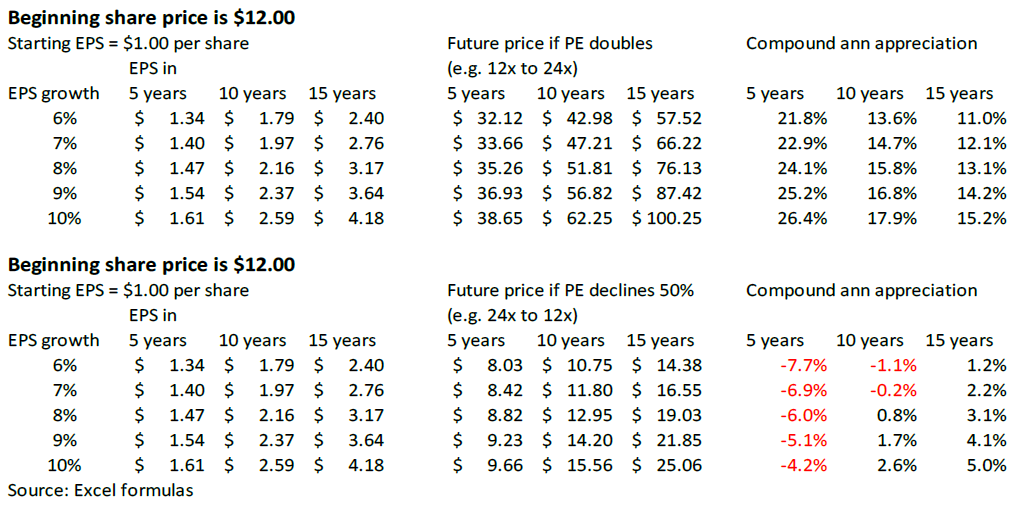

Below are two hypothetical examples. In the top of the table, the PE ratio doubles and therefore, investors enjoy a tailwind. In the bottom portion, the opposite occurs. The PE ratio declines by 50% (24x to 12x in this example) over the specified time period. If the change in PE occurs in a short period (e.g., 5 or fewer years) the impact is greater than when the change in PE is over a longer time period. I have placed additional comments on this subject in an endnote.i

As you can see, the EPS growth rates and time periods for the top and bottom portions of the table are the same. The big difference is the PE ratio doubles in the top portion, and it is reduced by 50% in the bottom portion. The impact on price change over the ensuing 5, 10 and 15 years is stark. For instance, if the EPS increases at an average rate of 6% annually for 5 years and the PE doubles, the gain is 21.8% per year. The price at purchase is $12 and grows to $32.12 in 5 short years. On the other hand, if the PE for this same stock contracted by 50%, the annualized loss would be -7.7%. Even with annual growth of 6% in EPS, over a 5-year period (the price falls from $12 to $8.03). While timing is hard to do, investors are well-served to pay close attention to valuation when making purchase and sale decisions.

There are many factors that can cause significant increases or decreases in price levels for major market segments let alone individual stocks. As you might expect, GDP growth (e.g., a measure of change in economic activity) is obviously a big factor. Healthy GDP growth tends to get mirrored in things like corporate sales and earnings. Indeed, when the economy grows at an above average rate, corporate earnings can be even more robust due to a tendency for profit margins to increase. That increase in growth is noted and appreciated by investors who are comfortable paying more in terms of PE ratios because they come to expect healthy future EPS gains. The problem of course is elevated valuation metrics are dependent upon favorable trends continuing. When economic conditions slow, let alone deteriorate, valuation metrics like the PE ratio can contract – at times sharply. So what might lie ahead? No one has a crystal ball, but well-known and reputable firms make estimates of future investment returns by modelling things like the likely change in earnings and changes in things like the PE ratio. In the short term – a year or 2, it is hard to estimate these changes with precision. There are too many external factors that can change perceptions and reality. However, as Ben Graham (Warren Buffett’s mentor) posited, “In the short run, the market is a voting machine, but in the long run it is a weighing machine.” Said differently, emotions can and often do trump reason, but ultimately reason prevails.

Elevated valuation levels become headwinds for future gains and vice versa

It's hard for segments that have enjoyed significant increases in valuation to maintain an upward, healthy trajectory. That’s because, life interferes - wars, pandemics, sharp bouts of inflation and/or sharp drops in economic activity (among other things) rattle markets. Often the very stocks and market segments that have been the most rewarding and truly easiest to own are those that decline the most when the tide shifts.

Long bull runs are preceded by and followed by periods of significant price declines. Investors are well- advised to understand that markets are cyclical. Below average returns and sharp declines often coincide with subpar economic conditions that cause earnings per share to slow if not decline outright. Conversely, periods of PE expansion translate into increases in aggregate market value relative to GDP. The opposite is true when aggregate valuation for stocks is low – so too in the market value to GDP ratio. Investment flows data reveals most investors add aggressively near what prove to be market tops and vice versa. This is the opposite of buying low and selling high. Realized returns by many investors are often nowhere near, and often well below, the returns for the segments and/or investment managers themselves.

As you likely know, many reputable firms estimate future returns for various asset classes over the next 5, 7, 10 or more years. Clairvoyance about the near and longer-term future is illusory. That’s because -

- Economic cycles and things like inflation, GDP can vary widely in terms of duration and magnitude of change from interim highs to subsequent bear market

- Stock market cycles tend to be even more volatile up and down due to expansion and contraction of profit margins and even more impactful, changes in things like the PE and other valuation metrics can travel dramatically higher or lower than longer-term norms.

Nevertheless, modelling what might happen in capital markets over 5 or more years can be a useful construct to aid one’s allocation decisions. As I have shared repeatedly, the only returns we can capture are those that lie in the future. No one knows precisely what lies ahead for the economy and markets, but it is nevertheless important to ‘model the math.’ A focus on current valuation and formulation of reasonable estimates for future EPS change are necessary to develop a framework for making prudent allocation decisions.

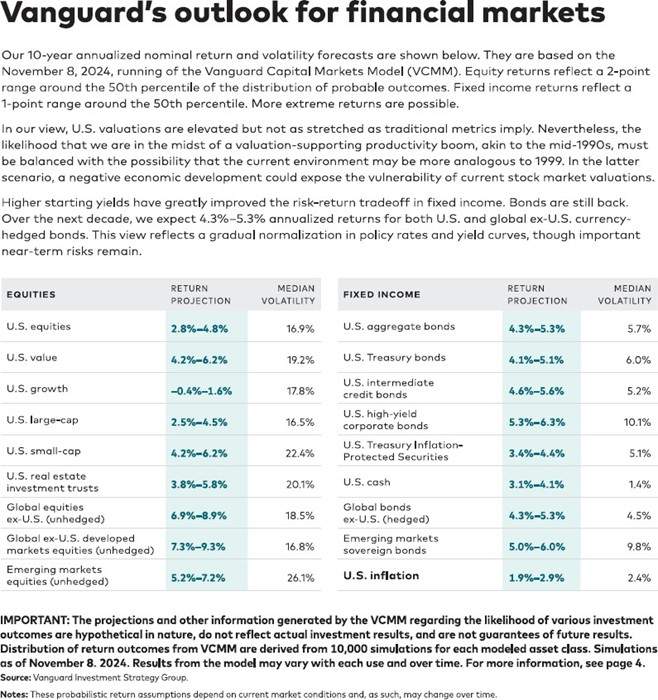

At the top of the next page, please find Vanguard’s estimates for prospective returns for various market segments over the next 10 years.

Here are a few comments that may aid your review -

- Things won’t move in lock step – there tends to be a lot of movement along the way

- Segments can remain in and out of favor for several more years before changing direction

- Some of these estimates will prove off the mark for a variety of reasons

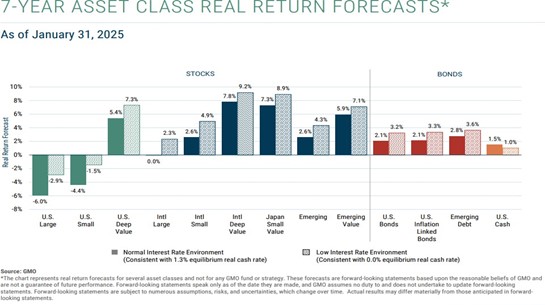

That said, if these estimates are directionally correct (e.g., within the U.S. we will likely see higher returns for value versus growth, mid and small caps versus large and international stocks versus U.S.) investors will be well served to allocate broadly beyond just U.S. large caps. As you know, our ‘stock in trade’ (pun intended) is to always hold diversified allocations. I have also placed another reputable firm’s recently released 7-year year forecast in an endnote.ii

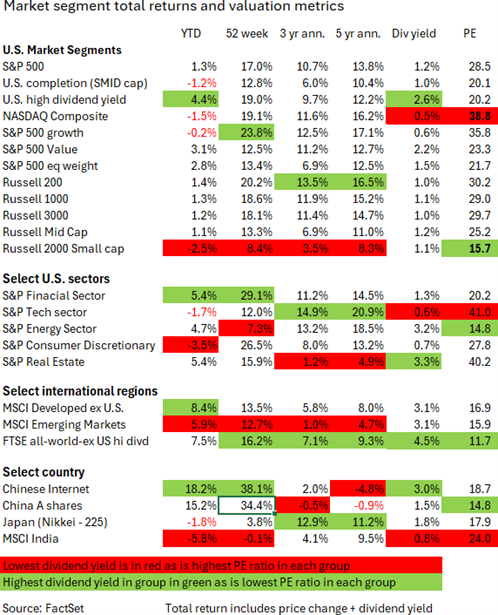

The table below shows the performance of major market segments thus far this year, the past 12 months, 3 and 5 years as well as their PE ratios and dividend yield. As you will see, some segments that have performed very well in recent years have advanced only modestly thus far this year. Other segments that have performed far less well over the many years are doing well so far this year and/or the past 52 weeks. Whether this is the start of a new trend is unknown. We believe changes in leadership often occur when they are least expected.

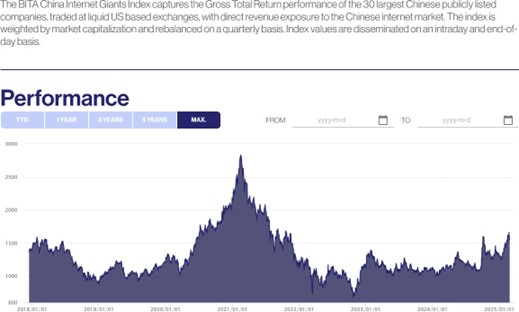

We do not know what lies ahead for the balance of this year or over the next few years. We do know that at what prove to be major inflection points that most investors have historically been over allocated in segments that have been most pleasing to own and have little if any allocated capital in the segments that surprise on the upside. Nearly a year ago (e.g. April 2, 2024) I shared data on Chinese tech stocks. Their individual and collective stock performance had been poor for quite a few years. However, their reported earnings per share were favorable and their valuation metrics were quite low on an absolute and relative basis. I have included a table that shows the chart and a performance summary for the Chinese Internet Index in an endnote.iii

Summing things up

We believe allocating broadly and then largely letting nature take its course is inherently sensible. That’s because over years and decades, stock segments (let alone individual stocks) can go up a whole lot more than they can go down (e.g., $100 invested in XYZ market segment could fall to $0 but it could also increase 10, 20, 50 or more-fold). As I have shared previously, over extended periods of time, winners overwhelm losers and drive results for the entire diversified portfolio. Exercising patience and largely letting nature take its course sounds like a passive approach, but we believe it beats most alternatives for growing one’s capital over decades while simultaneously reducing the risk of incurring unacceptable outcomes. Highly concentrated portfolios provide a greater array of outcomes – some better but many worse.

Because the future is unknown, investors are well-served to allocate capital into market segments that perform differently over time. Along the way, we also believe it makes sense to actively seek to identify market segments that have favorable valuation metrics. Often this entails investing in segments that have performed poorly of late or even for a number of years. An appreciation for the role of valuation can aid effective, albeit not clairvoyant decision making.

As always, we welcome your questions and perspective. Lastly, please know that we would welcome the opportunity to see if we could be of service to any family or friends who might find our approach appealing.

Warmest regards,

Richard Jones, CFA

Partner, Harmony Wealth Partners

i Over the course of my career, I have enjoyed a front row seat to periods of significantly expanding valuation metrics. A 3x increase in valuation from 10x to 30x (or 15x to 45x) translates into a 6-fold increase in price when underlying EPS doubles. Because valuation metrics tend to wax and wane, I find it sensible to be cautious with respect to allocating into segments that have experienced significant increases in valuation metrics. Conversely, I appreciate the potential benefit to leaning into segments that have fallen or at least languished due to large valuation declines. That’s because if a segment goes from a PE of 36x to 12x while underlying EPS, doubles, the price will decline by 1/3 (e.g., from $36 to $24). Importantly at some point, that same security may be poised for significant gains if the PE multiple subsequently expands.

ii

iii

Source: bita.com

The chart on top reminds me of the NASDAQ index a couple of decades ago. In the late 1990s, it rose sharply fueled by sharp increases in its PE ratio. It subsequently lost 80% of its price in the tech driven sell-off from March 10, 2000 through October 9, 2002. At the bottom of that bear market period, valuation metrics were very low (as was investor confidence) and the index has gone on to post stout gains since then and since the bottom of the GFC (Global Financial Crisis) in March 2009. Are there differences between the two indexes? For sure there are. That said, history reveals that that high to low swings can be vertigo inducing, but recoveries can be powerful too. Over the past 7 years, the BITA China Internet Giants index is up only 2.76% annually. From its February 16, 2022 high ($2832.83) it fell 75% to its October 31, 2022 low ($707.62). When valuation multiples fall precipitously, prospective rewards can be very high and vice versa. As the table above shows, it is up 51% over the past 12 months and over 100% from its October 2022 low.

The foregoing information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that it is accurate or complete, it is not a statement of all available data necessary for making an investment decision, and it does not constitute a recommendation. Any opinions are those of the author and not necessarily those of Raymond James. The Dow Jones U.S. style indexes are derived from the Dow Jones Global Indexes (DJGI) U.S. country index, which covers approximately 95% of the float-adjusted market capitalization of the U.S. stock market: Stocks representing, approximately, the top 70% of float adjusted market cap are classified "large-cap", the next 20% are classified "midcap" and the remaining stocks are classified "small-cap". In each size category, a multivariate statistical procedure is conducted using six factors as inputs to generate three categories: growth, value and neutral. Example: Dow Jones US Large Cap Growth Index, Dow Jones US Large Cap Value Index, Dow Jones US Small Cap Index. The S&P 500 is an unmanaged index of 500 widely held stocks that is generally considered representative of the U.S. stock market. The NASDAQ composite is an unmanaged index of securities traded on the NASDAQ system. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected, including diversification and asset allocation.