Economic Concept: Monopoly – It’s No Game

I remember playing the game “Monopoly” as a kid. Besides the fact it seemed like the longest game EVER, it was clear that to win you had to gain financial control of the board, until you had the power to put your competitors out of business. In a free-market economy, this is very hard to do (at least for very long) and that is a good thing. In the real world, even if a company is able to put their weaker competitors out of business, they will soon find that new competitors evolve, which are even more efficient adversaries. So in real life, monopoly is no game!

Okay, so far I’ve explained how competition is necessary for the efficient allocation of scarce resources. When two or more parties compete to earn the business of a third party (remember, this is known as “an economic exchange” for the $2 readers), they must offer the most favorable terms to succeed. In the case of producers (manufacturers), they must compete by offering a better product than their competitors (at the same or lower price).

Sometimes, a producer of a good or service has no competitors and there aren’t any close substitutes for their product. In this case, where there is only one producer, a monopoly exists and the market works very differently.

Without competition, the producer has no incentive to produce better products at lower prices; therefore, they simply set a price above what the market price would have been, in order to earn a higher profit per unit. At that higher price, consumers may demand less of the product/service than they would have at a lower market based price; but that’s okay to the monopolist, since they can still generate higher profits while having to produce less. Not a bad arrangement if you can keep it.

In a free market, it is rare for a monopoly to last long. The lure of these higher profits attracts new producers. In the long run, rules, regulations and government coercion are required to protect a monopoly from new competitors (which wouldn’t really constitute a free market at that point anyway).

In the case of a monopolistic business, supply and demand does not balance at the same price that a competitive market would produce. As we have discussed, the most efficient allocation of resources occurs at the price where the quantity supplied by producers equals the quantity demanded by consumers. The dynamic process of competition provides the incentives for prices to move to that precise level. However, monopolies set their price ABOVE the “market” price (because they can), and only have to produce just enough goods and services demanded by consumers at that higher price.

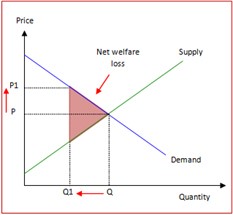

In the illustration below, free-market supply and demand meet where “P” price and “Q” quantity meet. A monopoly, however, will set a price higher than “P”, such as “P1.” So if you look at the chart, “P” is where the price should be and “P1” is where the monopoly chose to price their product or service, because there was no fear of losing any business to another company.

Looking at the chart above, again. The quantity demanded by consumers at this higher price would then be “Q1” (less than “Q”). Even though the monopolist benefits from this situation; its gain is not as large as the consumers’ losses. This results in a net loss to society (represented by the shaded area). In other words, there was no satisfaction met for ALL the consumers who truly wanted the product or service, because it was artificially priced out of their range.

Other Variations of Monopolistic Practices

There are some variations to the purely monopolistic condition. Here are some others to consider:

- Oligopolies are when only a few producers exist; therefore, they have some pricing power.

- Cartels exist when all producers of a good or service work together to coordinate a higher price by agreeing to limit production; therefore, artificially lowering supply for a high demand (think OPEC).

In any case, whenever a price is artificially set above the price that would result from true competition, the total standard-of-living of the economy suffers and resources are allocated less efficiently.

Centrally-planned economies suffer from these same results. In these societies, prices are also set in an artificial manner (although, not always higher than the free market prices), resulting in a net loss in standards-of-living, due to an inefficient allocation of resources. When central planners arbitrarily set prices, they are creating many of the same effects that result when monopolists set prices.

This is why choice is so important. The more choices you have, the more a business has to attract your attention. They do so by making you a better deal: lower price and/or better product. This winning formula only exists in a free market; which is why I’ll take free-market competition any day.