It’s an election year, which means you can expect to hear presidential candidates being asked about their plan for preventing Social Security from going bankrupt.

While you may not hear a clear answer, you can rest assured that Social Security is not going bankrupt.

Social Security benefits are primarily funded by the payroll taxes collected from today’s workers. Money goes into a pot called (believe it or not) the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund, and benefits are dispersed from there. It’s a pay-as-you-go system, so as long as workers are paying payroll taxes, Social Security benefits will be paid.

The problem isn’t bankruptcy – it’s that the program faces a long-term funding shortfall that, left unaddressed, will mean a reduction in benefits for future retirees.

For every person drawing Social Security benefits, there are just 2.7 workers paying into the system.

For decades, the Social Security system collected more in payroll taxes and other income than it paid out in benefits, building up a large reserve. In 2021, when the program’s costs began exceeding its income, Social Security started drawing from this reserve fund to make up the difference. When those reserves are depleted – an event expected in about 10 years – benefits will be reduced by an estimated 23%. If Congress takes no action to head this off, people who are 57 years old today will receive 77% of today’s benefits when they reach regular retirement age.

For the average dual-income couple retiring in 2033, that’s $17,400 less.

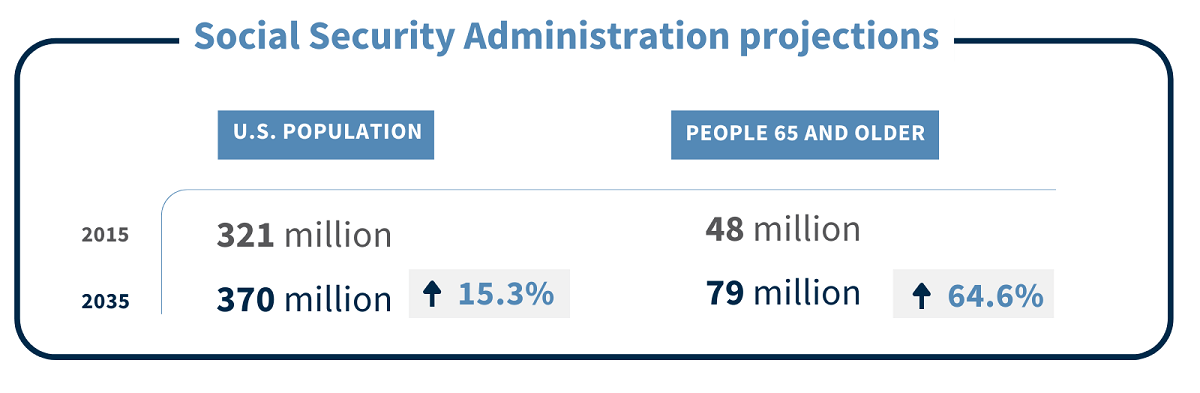

The problem is mostly a demographic one. In 1940, a 65-year-old had a life expectancy of less than 14 years. For today’s 65-year-olds, that expectancy has increased to 20, and a staggering 10,000 baby boomers are retiring every day.

At the same time, younger generations are getting smaller, which means fewer workers paying into Social Security. In 2022, there were just 2.7 workers paying into the program for each person drawing Social Security benefits. By 2035, that number is projected to go down to 2.3.

Additionally, a smaller percentage of Americans’ income is subject to the payroll taxes that fund Social Security because the earnings of the highest-paid workers have grown faster than those of the average worker. In 1937, 92% of earnings were below the taxable amount. By 2020, it was just 83%.

Since 67 million Americans receive Social Security payments each month – it’s the main source of income for people 65 and older – it’s not hard to see why politicians are on the hot seat about fixing it.

To patch the shortfall, Congress has a few options – none of them particularly appealing.

The most obvious way to increase funding to Social Security is to raise payroll taxes. Currently, employers and employees each pay 6.2% for Social Security. Increasing that rate to 7.75% could assure solvency for 75 years. However, this solution may be unaffordable for lower-income workers.

Another option is to add new tax sources. One possibility, floated by the American Academy of Actuaries, is to tax investment income or increase estate and gift taxes – an idea that’s likely to face resistance.

The Social Security tax rate applies only to annual wages currently set at $168,600. If Congress removed that cap and taxed all earned income, the additional revenue would wipe out 78% of the shortfall. Traditionally, earners above $160,200 are subject to a wage cap to prevent higher taxation that may not justify the benefits. Social Security’s political support comes from the idea that you can receive back a benefit you have paid into. Not capping the amount subject to taxation would fundamentally alter the program and political support.

Another idea is to reduce benefits for high earners who aren’t yet eligible for Social Security – not those who are already collecting – based on the idea that those people will be less reliant on those benefits. However, this measure alone would not curb Social Security expenditures enough to address the problem.

Arguably the most popular solution is to raise the retirement age. Today, Americans can start collecting Social Security benefits at 62, but the benefits increase the longer you wait, reaching a maximum monthly payout at 70.

The full retirement age (FRA) was 65 for much of the program’s existence. Today, FRA is 66 years plus two months for people born in 1955, and increases gradually to 67 for anyone born in 1960 or later.

Some lawmakers advocate for increasing FRA to 70 to bring it in line with today’s longer life expectancy. This change alone could eliminate nearly a third of the Social Security trust fund’s 75-year deficit. However, having to work to an older age could be especially challenging for low-income Americans and people working in jobs that are physically demanding.

The last time Congress overhauled Social Security was in 1983, when the program was just months away from not being able to pay full benefits. The Democratic House, Republican Senate and Republican President Ronald Reagan agreed to gradually raise the full retirement age from 65 to 67, which was reached in 2022. This effectively cut benefits by 13% while increasing payroll taxes.

Odds are a solution would comprise some combination of these actions – higher taxes for some, lower benefits for some and more years on the job for some. And any proposal is likely to face stiff political opposition

The sooner policymakers act, the more options they will have, and the more time pre-retirement Americans will have to prepare for changes. Acting early allows for any tax increases or benefit reductions to be phased in gradually (rather than, say, implementing a 25% payroll tax increase come 2034). Early action would also enable lawmakers to make adjustments for people who will start receiving Social Security benefits within the next 10 years, before the reserves run dry.

One thing’s for sure: The longer they wait, the more abrupt and painful the changes will be.

Sources: ssa.gov, newsweek.com, npr.org, Investopedia.com, cnbc.com, money.com, cnn.com, cbpp.org, asppa.org