Sharing knowledge and experiences

“Art enables us to find ourselves and lose ourselves at the same time.”

– Thomas Merton

Risk & Return

A definition of risk is, “The possibility that something bad or unpleasant will happen”.

Well, duh!

There are actually two general categories of risk.

One risk is the risk of loss no loss. Insurance is generally in this category. You either have a fire or you don’t have a fire. There is no “win” or gain side to this kind of risk.

The other kind of risk is the risk of win or lose gain or loss as in investment risk.

During the height of COVID we were all acutely aware of risk. There is the risk of getting it, the risk of giving it, the risk of suffering from it. And, of course, that risk of loss — the loss of a loved one, the loss of a job, the loss of our finances and on and on.

So what do we do about risk?

An Apollo engineer (remember the Apollo space missions) was noted as saying, “There is no such thing as a leak-less valve. The best you can do is control the leak to an acceptable level.”

Sound advice.

So how do we “control” an acceptable level of risk?

Good question.

Part of the answer may come from an understanding of how much risk we’re willing to take (or think we’re willing to take). I’m willing to drive 75 mph but not 85. I’m willing to climb Mt. Whitney at 14,505 Ft. but not Mt. Everest at 29,029 (imagine that last 29 feet). Interestingly 90% of mountaineering accidents happen on the way down.

Some risks we can easily determine not to take. But investment risk is not so easy. We can put all our money in a can in the back yard but after inflation we’d be losing money, losing purchasing power. So there’s that risk.

Often there are different risk questionnaires or surveys that can help. However, as is often the case none of us really know how to answer these questions to give an accurate picture of our risk tolerance, as much as we try. We can answer any number of risk questionnaires and surveys, determine our risk parameters, diversify our investments accordingly with the hope that this allocation will behave within those parameter. As an aside, it’s interesting how people answer risk questionnaires at different times. When times are good, things are up, taking more risk can seem more comfortable. When times are not good our responses are much more guarded and we get much more risk averse.

Goldilocks doesn’t seem to exist in the investment world, as much as we try to find her.

No matter how we answer the question of acceptable risk there can still be surprises. These are what we call Black Swans.

“The phrase 'black swan’ derives from a Latin expression; its oldest known occurrence is from the 2nd-century Roman poet Juvenal's characterization of something being 'rara avis in terris nigroque simillima cygno" ("a rare bird in the lands and very much like a black swan").[3]:165[4][5] When the phrase was coined, the black swan was presumed not to exist. The importance of the metaphor lies in its analogy to the fragility of any system of thought. A set of conclusions is potentially undone once any of its fundamental postulates is disproved. In this case, the observation of a single black swan would be the undoing of the logic of any system of thought, as well as any reasoning that followed from that underlying logic.

Juvenal's phrase was a common expression in 16th century London as a statement of impossibility. The London expression derives from the Old World presumption that all swans must be white because all historical records of swans reported that they had white feathers.[6] In that context, a black swan was impossible or at least nonexistent.

However, in 1697, Dutch explorers led by Willem de Vlamingh became the first Europeans to see black swans, in Western Australia.[7] (SOURCE: Wikipedia)

So how do you prepare for a black swan event? By definition you don’t. You can’t know what is unknowable — until it’s knowable and then it’s too late. The best you can do is find and acceptable level of risk you think you can know and you think your finances can cope with and manage the “leaks” from there … and often.

While we try to understand risk and risk-tolerance perhaps another way of thinking about all this is stress testing. This concept is acutely sensitive to our current other life, our lives outside our investments and finances. Have you ever noticed that when we’re not feeling well we can become impatient, cranky, maybe half-empty about everything? (Or is it just me?)

The point is, completing a risk-tolerance questionnaire (or a stress-test questionnaire/survey), important as they are, can produce different results depending on our current state of our mind.

But at any level of acceptable risk how do you manage or control the leaks?

One way we at least try to estimate the “leak” (risk) is through back-testing an investment or portfolio. How would this investment or mix of investments have performed on, say Monday, Oct. 19, 1987 when the Dow Jones Industrial Average went down 25% … in one day? Or from Sept. 2008 to January 2010? Or March 2020?

Of course, past performance is not guaranteed in the future and for these and other past crashes, thank God, huh? The question is, what of the future? Well, we know we can’t predict the future as much as many have tried. All we have is the past. So when we try to look into the future we generally end up with probability sets based on the past.

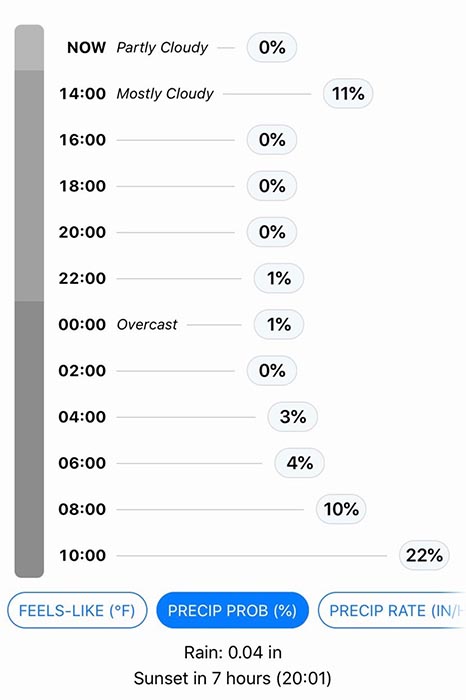

For instance, there’s a 11% probability it will rain tomorrow evening as this weather app suggests.

We might be very confident that it probably will not rain every day for the rest of our lives. I mean, what are the chances of that happening? What’s the probability? But what of the times when the probability of rain is high … and there will be a lot of it?

A friend who had breast cancer was told if she followed through with the radiation program after her surgery she’d have less than a 5.0% chance of re-occurrence, down from a 33% probability. Certainly 5.0% is better than 33% but it’s not zero.

Do we need zero? Remember, there is no such thing as a valve that will has zero leaks.

In investing we use different metrics to try to determine probabilities of future outcomes.

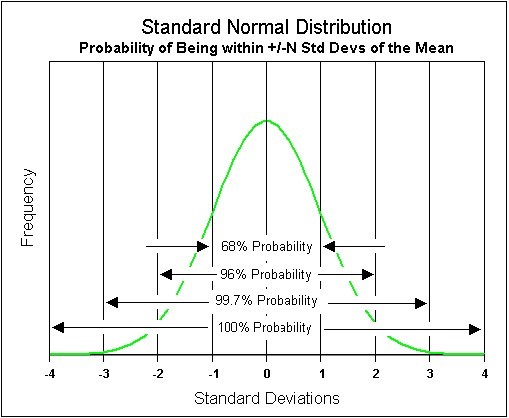

We’ve all heard of Standard Deviation. Standard Deviation presents us with this: The graph above suggests that 68% of the probable returns should occur within one Standard Deviation, 96% of the probable returns will occur within 2 Standard Deviations and 99.7% of the probable returns should occur within 3 Standard Deviation. And then beyond that are what we call the “tails.”

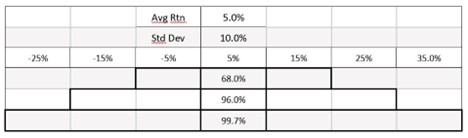

EXAMPLE: A portfolio has an expected annual return of 5.00% and a Standard Deviation of, say 10%. It would look like this.

So you get some idea of the expectation of downside and upside within these parameters – we would expect a return between -5% and +15% 68% of the time.

We would expect a range of returns between -15% and +25% 96% of the time. And so on.

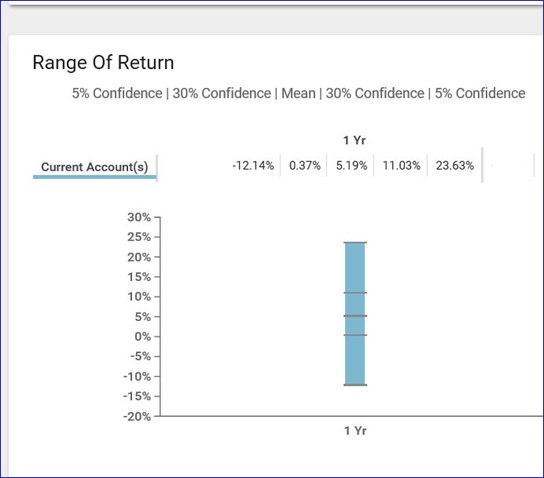

Here’s another similar example — it's a hypothetical portfolio with an average expected return of 5.19%. With 1,000 Monte Carlo return simulations there is a 5% probability or confidence level that the portfolio, in any one year, could go down-12.14% … or more.

SOURCE: Raymond James Portfolio Management

This hypothetical graphic also suggests a 5.0% probability that this portfolio, in any one year, could be up 23.63% or more.

But what about the “or more”? What about those tails where Black Swans swim?

Kinda important, especially on the downside.

Can we move the dial to 1.0% probability? Would that information make us feel better? For instance, say there was a 1.0% probability your portfolio could lose 25% … or more.

Would that help? But remember, the “or more” can be the Black Swan which, by definition, no one can predict because you don’t know what’s out there.

Here’s another approach or view of risk metrics, we call it “time diversification.”

We all have some concept of the idea of investment diversification — not having all of our eggs in one basket so we diversify among stock, bonds and cash, etc. But “time diversification” suggests that your risk of loss is muted, if not even eliminated, the longer you stay in your investment portfolio.

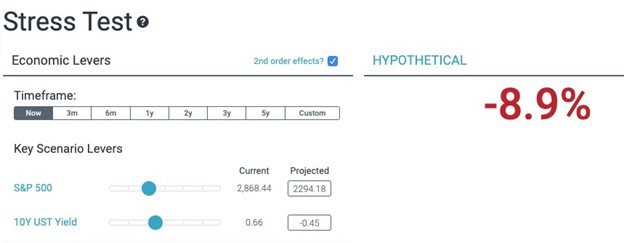

Looking at a hypothetical portfolio of 50% stocks we can ask, how would this portfolio react if the S&P 500 were down-20%, that is dropped from 2868.44 to 2294.18?

The immediate response would be -8.9%.

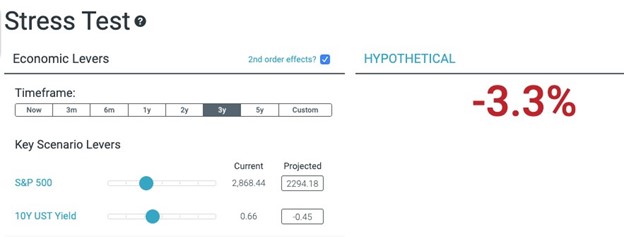

But if we hold this hypothetical portfolio for, say 3 years?

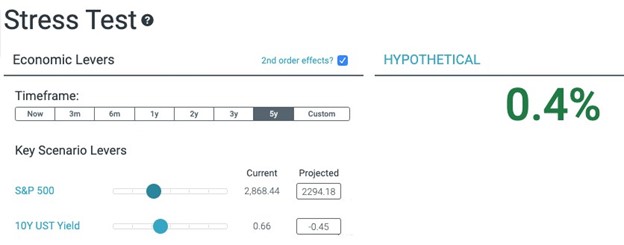

And if we held this hypothetical portfolio for 5 years?

SOURCE: Hidden Levers

PLEASE NOTE - this is NOT your portfolio nor is it any portfolio with 50% equities because the character of the equities and other investments in the portfolio matters.

The point is, time matters. In fact, there’s an old saying, “It’s not timing the market but rather time in the market that builds wealth.

Another important aspect of risk of course can be fear.

We all relate to fear differently. When we feel we’re the only one at risk we can feel differently from when everyone is being affected by the same risk. It doesn’t mitigate the risk but it may mitigate our fear.

During COVID we were all being affected by the same risks and there is some odd comfort in that. Okay, maybe not comfort but more manageable discomfort.

In closing I’ll leave you with this from my esteemed colleague and partner, Lisa.

“Everybody’s comfortable until they’re not.”

Lisa Barrantes, CRPC, ChFC, CLU, CASL; Financial Advisor

NEUNUEBEL BARRANTES WEALTH MANAGEMENT GROUP of Raymond James

I know all this is pretty arcane stuff, but it’s what we do … so you don’t have to.

At issue with all this is to find an acceptable level of risk, or to use the Apollo analogy, an acceptable level of leakage.

It all depends on our risk and stress tolerance and these different risk measures try to give us some idea of how much leakage a portfolio might have.

But remember too, the other side of downside is upside.

The goal of portfolio management is to find an acceptable place to live within a given range of return guesses. The purpose is to determine, with some probability of success, how we can evaluate your income and spending levels, consider a range of returns of your investments and come to some acceptable probability of your living happily ever after.

Hang in there.

And remember, America is a society not an economy.

Sincerely,

David, Lisa & Cydnet

Scenarios described are hypothetical and are for illustrative purposes only. Information contained herein was received from sources believed to be reliable, but accuracy is not guaranteed. Information provided is general in nature. Investing always involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss. No investment strategy can guarantee success. Past performance is not indicative of future results.