On the Money Couch

What does your past reveal about your relationship with money?

By Josh J. Miles

The first time I remember having to manage any money – greater than my weekly allowance that scarcely covered lunch off of the dollar menu at McDonalds – was when I went off to college and was working part-time while going to school. I still remember going to the ATM to pull out $40 and using the ATM receipt to record how I spent every penny ($0.89 on pack of gum, $2.99 for a burrito, etc). I would then enter that data into my newly acquired Quicken program each evening. When my girlfriend, now wife, would come to see me and we went to lunch, I would simply keep the receipt tucked in my jeans so I could “reconcile” later without scaring her with my obsession to keep track of every dollar. It was not until years later – after many arguments about money with my wife – that I truly understood why I was so diligent (read: controlling) with money. Like many long-term marriages, we had our go-to disagreements about trivial things, but we seemed to have a common theme: money.

It was not until we attended a “marriage intensive” in Texas that I began to understand my unhealthy relationship – with money. It was during this 4-day experience when our coaches had us break down our past experiences that I realized how much it shaped who I am today (I will stick to money in this thread, but let’s just assume I had more to work on than just my relationship with money)! However, it was this exercise that helped me understand myself better(I will come back to this exercise later).

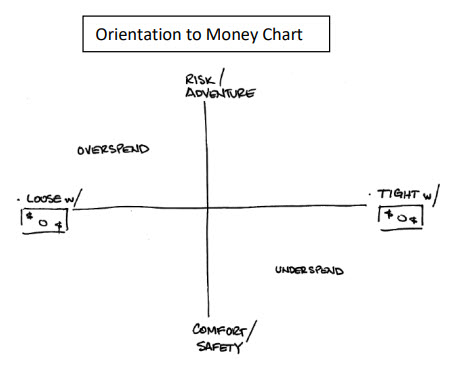

A study done by MIT AgeLabs’, Dr. Joe Coughlin, suggests that your relationship with money is developed between the ages of 5 and 15 years old.1 I have asked many of you to chart yourself on the “Orientation to Money” chart (right) to help each of us better understand our gut-level relationship with money. Regardless of whether you land in the extreme northwest corner (freespirt) or the extreme southeast corner (conservative2 ), you can be an informed investor – it is just important to understand yourself (and your partner) so we can all strive for a healthy balance (near the Orientation to Money Chart center). MIT AgeLab suggests this orientation is most likely a result of observing and learning from how your family of origin handled money.

During our intensive, I was asked a question that helped me understand myself better than I ever had before. It was simply this: “what did you learn about marriage from your family?” They then introduced several aspects of marriage that are modeled to us by our own parents, such as communication, finances, roles and responsibilities, etc. The proverbial lightbulb turned on and I realized how much a product of my family I was. Now, for my mom and dad, this is neither negative or positive, it just explained so much about the way I choose to respond to my environment (positively and negatively).

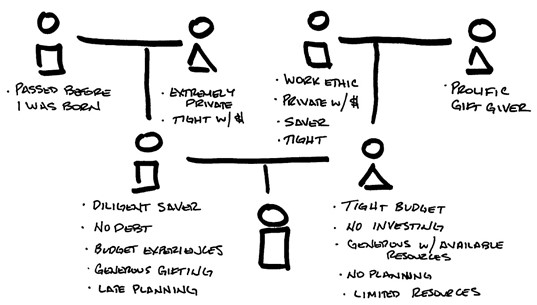

The question about money applies to our conversation today, and MIT AgeLab has built a similar exercise that I believe is something we can all learn from. They call it the Money Genome Project. It is a simple exercise that, done by yourself or with your significant other, can truly help us understand ourselves so much better. Here is how it works:

- Draw out your family tree – those individuals that had an impact in how you were raised to see money.

- Next, write a few key words to describe what you learned in the following five areas:

- Spending

- Saving

- Investing

- Gifting

- Planning

Example:

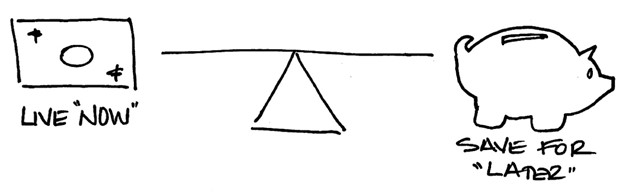

The example above is my Money Genome. It might not be surprising after looking at this that my own orientation to money has a tilt toward being tight with money. I love “experiences,” but I would rather do them on a budget. As a financial advisor, saving, planning and investing are extremely important but only to the point where it allows my family and me to balance “living now” with “saving for later.” I grew up with very limited resources, so we have been less restrained with money than my previous generations were when it relates to experiences. For me, the experiences I did have as a kid are seared into my memory and I want the same for my kids. Also, I have had the benefit of seeing many of my clients work hard during their careers – delaying gratification through saving while passing up experiential opportunities – only to pass before they could benefit from their diligence.

I encourage you to spend some time mapping out your own money genome. If you have a partner, do this together. Discuss how your family history and lived experiences inform how you handle money now. Do you see a correlation to how you mapped yourself on the “Orientation to Money” chart discussed above? Having this baseline understanding will help you see where your biases toward money come from. Remember, there is no perfect orientation to money. When we have this understanding, it will help us overcome some limiting beliefs and move us toward the center between “living now” and “saving for later.”

While our money genome helps us see what we learned about money from our family of origin, I would be remiss if we did not point out six major factors that also have varying degrees of influence on our relationship with money:

- Race/Culture

- Religion

- Social Class

- Money Events

- Generation

- Gender

These factors undoubtedly show up in our money genome, but it can be helpful to see the behaviors of our elders through these macro lenses. How are these factors changing in your experience? Which of these factors are playing strongly in your own orientation? The challenge is to separate myth from truth.

As an example:

Myth: Men are better with money.

Fact: Gender has zero correlation to money competency.3

To summarize today's discussion, I want to emphasize a few key points:

- We are all a product of our past. Understanding our gut-level orientation to money will help us understand what is healthy and what we may need to modify to provide greater balance and freedom in money decisions.

- Be aware of your feelings. Remember, emotions provide context and valuable information. However, be willing to analyze these feelings and where they come from. Are they applicable to the decisions we are making with money? Can we adjust our orientation to better reflect the balance we want to attain in our financial lives?

- A financial plan is essential. The goal of any financial plan should be to provide a framework to help make better lifelong decisions. It will help you see if you are balancing “living now” with “saving for later.” For example, if we take a trip to Europe next summer, how does that impact our ability to reach our retirement goals? It may mean working an additional 3 months after our goal retirement date. But we are able to take a trip with our kids, while they are are still at home and make memories with them. In our house, that is a resounding – YES – I will work longer to build those memories! Until you have your own plan built, you will not have the ability to weigh your “trade-offs.”

Our hope is that through your relationship with us and our focus on planning with you, we can help you in your pursuit of a well-planned, balanced financial life where we can help you reach your financial goals with confidence. For many of us, this will require some time on the money couch, unpacking our relationship with money, sifting through the healthy and unhealthy biases we all carry. If you feel like you need a money “intensive” of your own, we are here to help!

Best Regards,

Josh J. Miles, CPWA®, BFA®

Managing Director – Wealth Management

Financial Advisor

Raymond James & Associates, Inc., member New York Stock Exchange/SIPC

Notes:

- MIT AgeLabs. Hartford Funds. Episode 80: The Human-Centric Investing Podcast

- Conservative is not the actual term for a preference for a tight/safe orientation to money. It actually presents itself as “control” as the fear drives those of us with that orientation to protect money in a less than optimal way.

- A Field Guide to Lies. Daniel J. Levitlin

The information contained in this report does not purport to be a complete description of the securities, markets, or developments referred to in this material. The information has been obtained from sources considered to be reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing material is accurate or complete. Any opinions are those of Josh Miles and not necessarily those of Raymond James. Expressions of opinion are as of this date and are subject to change without notice. There is no guarantee that these statements, opinions or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct. Holding stocks for the long-term does not insure a profitable outcome. Investing involves risk and you may incur a profit or loss regardless of strategy selected, including asset allocation and diversification. This is not a recommendation to purchase or sell the stocks of the companies pictured/mentioned. Past performance does not guarantee future results. Future investment performance cannot be guaranteed, investment yields will fluctuate with market conditions.